BY HAJJARAH NAGADYA

HIV is not just a health issue but a multi-sectoral issue that requires many different players. Is the UNAIDS HIV ’90-90-90′ fast-track initiative in Uganda achievable?

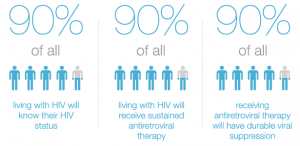

UNAIDS has announced that by 2020, 90% of all people living with HIV should know their HIV status, 90% of all people diagnosed with HIV should receive sustained antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 90% of all people receiving anti-retroviral therapy should have achieved viral suppression. By 2030, these targets are all raised to 95%. This is goal of the Fast Track initiative.

Many countries have welcomed and embraced this ambitious target, but the question is whether it is possible to do so. This is a target that everyone wants to achieve if we are to reduce HIV prevalence, but are we ready as countries to achieve this? In order to do so, people have to be tested, have to start treatment at some stage, and have to adhere to treatment, once started, for life. There are many serious hurdles they can meet along the way.

Testing is the first area of concern. We all know that early treatment can reduce rates of onward transmission by 90% in theory, because if people with HIV are able to adhere to their treatment our ‘viral load’ should drop to an undetectable level, meaning that we cannot pass on our HIV to anyone else – as if we should ever wish to. But how many countries have been successful in putting all people in need of ART on treatment? In Uganda, for example, over 1.5 million people are living with HIV but only 564,453 were on anti-retroviral therapy, as indicated in a 2013 HIV and AIDS Uganda country progress report. This same report revealed that only 71.7% of the total number of pregnant women tested for HIV were given ARVs during their ante-natal care. Thus we can see that some children will have been born with HIV, which will in turn create a bigger gap between the targets and reality.

In many health facilities with a huge number of pregnant women and very few health workers, group pre-counselling and testing is practised as opposed to individual counselling followed by testing – which is what is meant to happen. One-to-one counselling is only offered just before handing over the test results. Group-counseling is in the form of a health talk. This is not adequate enough for someone who is testing for the first time. Because of the impersonal nature of group – as opposed to one-to-one-counselling – women are often not prepared for what may be ahead of them. This has created an environment where many women run away before receiving their test results, and others do not carry on taking their drugs after being found to be HIV-positive.

Violence in the form of stigma and discrimination is also becoming a chronic characteristic in many settings. It stands as another serious barrier to achievement of this ambitious target, both in healthcare facilities and in families and homes.

The fear of testing is very real. Both men and women fear taking the HIV test because they do not want to be seen and gossiped about. Those who already know their status are afraid to start their medication and often hide while swallowing the drugs. This kind of fear has hindered adherence to treatment and leads to the failure to suppress the virus in their bodies. Violence and the fear of violence also marginalises people living with HIV and undermines the national prevention and treatment efforts. Until society understands that HIV is like any other disease, that it can be manageable and no longer a death sentence as it was previously referred to, the threat or reality of violence can also mean that this ambitious target may instead become a nightmare to haunt us.

In addition, donors are reducing their funding. and in Uganda we have failed to increase our domestic funding for health. In the 2015/2016 financial year, only 7% of the national budget was allocated to health, which is less than the Abuja target which proposed that countries allocate 15% of their national budget to health. We are very concerned that this will not be sufficient to achieve the Fast Track target if donors continue to reduce their funding while at the same time Uganda is not increasing the domestic funding.

Uganda is also still reporting cases of a lack of supplies. There are stock-outs of ARVs, despite the 2013 WHO treatment guidelines that recommend starting all people living with HIV whose CD4 counts are below 500 on ART. In addition, there are regular stock-outs of testing kits even though they are obviously essential as an entry point to HIV treatment.

Viral load testing in most of the low-income countries is still a dream. People are not even aware of what a viral load is, and are not in a position to pay for the test anyway. The test is widely charged for in Uganda although it is supposed to be free if donated by PEPFAR. There are just a few men – and even fewer women – in Uganda who are able to pay an amount of $50 to have their viral load tested. Until this service is made free for even the poorest people to access it, people won’t check their viral load, and it will be hard to understand whether the virus is being suppressed and whether the global target is being achieved or not.

So even though we know that about 550,000 of us so far have started HIV treatment, without routine viral load screening we have no idea how many of us have been able to adhere to treatment and thus have an undetectable viral load. Even the phrase “achieving viral suppression” – the one normally used by donors and policy makers – puts the blame on our shoulders if we don’t achieve it.

How fair is this allocation of blame?

Criminalisation also plays a part here. Countries have passed laws that criminalise intentional HIV transmission and attempted HIV transmission, despite the fact that we are still advocating for voluntary HIV testing. Such punitive laws are more likely to deter people further from accessing health services, including HIV testing. People work out quickly that no one needs to leave a trail that will be used by the law to count him or her out – and this includes pregnant women. People in these environments are therefore now more likely not to test, and are also likely not to go for treatment because according to our new law in Uganda, you can be convicted if you know your HIV status.

It is vital that people understand that HIV is not just a health issue but a multi-sectoral issue that requires many different players. The more people tag it to individuals, the more we need to talk not just about overcoming HIV and AIDS as a non-curable disease, but about overcoming violence against people with HIV in the form of stigma and discrimination.

Hajjarah Nagadya is a young woman living with HIV. She works for the International Community of Women Living with HIV in Eastern Africa. She has served on different committees that have voiced the concerns of women living with HIV, and was formerly a member of the UNAIDS Dialogue Platform for Women Living with HIV.

NB: This article was first published on the Open Democracy website